The Lord's Prayer and the Ten Commandments: Theme #9 of the Westminster Shorter Catechism

Posted by Andrew Miller on 27th Dec 2023

In the early years of my life as a Christian, I didn’t realize it, but I was trying to reinvent the wheel. I voraciously studied the Scriptures, but I approached them in an atomistic and unsystematic way, not being familiar with the covenants that unify the story of the Bible. I wanted to please the Lord, but lived as if I was the first Christian trying to figure out what to do. I was a bit like the Ethiopian of Acts 8:31, struggling to understand the Scriptures without a guide.

Thankfully, little by little, I became exposed to the writings of other Christians who have come before me and struggled with the same sins, wrestled with the same Scriptural quandaries, and passed along their wisdom. Their voices have been a great help, received with discernment and comparison to Scripture (Acts 17:11).

One such great guide to help Christians understand from Scripture how to live a life pleasing to God is the Westminster Shorter Catechism. It helps us by bringing Scripture passages on a particular topic together into one place—this is what we call “systematic theology,” or, as I also like to think of it “biblical reasoning.” As Michael Horton writes, “by systematic theology we refer to that task of harvesting the results of exegesis in order to display the logical connections and canonical coherence of biblical teaching.” Catechisms should be based on Scripture, even a kind of paraphrase of Scripture’s content. They have been called maps that survey the ground of Scripture and help a person to navigate the Bible.

While all that sounds academic, the Shorter Catechism is meant to be practical, which is why it devotes substantial time and space to explaining the Ten Commandments and the Lord’s Prayer. “Consider that 42 of the 107 questions in the Westminster Shorter Catechism explain the Ten Commandments (that’s 39 percent!)...”

While many today reject the Ten Commandments as belonging only to God’s Old Testament way of dealing with his people, the writers of the Shorter Catechism rightly recognized that the Ten Commandments summarized God’s moral law, which reflects his unchanging character. In other words, while the Old Covenant administration may have been surpassed, the moral law continues to show us how to please God. Likewise, Jesus explicitly taught us how to pray in the Lord’s Prayer.

It is important to note that the Shorter Catechism puts the gospel first. While the Shorter Catechism may not express the pattern of guilt-grace-gratitude as clearly as the Heidelberg Catechism does, it nevertheless makes clear that the Christian life is lived in thankfulness for what God has done for us in Christ. The explanations of the Ten Commandments and the Lord’s Prayer come after the great sections on justification and adoption and sanctification. They are a reminder of James 2:17: “Faith by itself, if it does not have works, is dead.” While many present that verse to guilt people into action, note the underlying good news: God gives his people a living faith, “a living hope” through the resurrection of Jesus (1 Peter 1:3).

In fact, the Shorter Catechism reminds us that our obedience to God’s law is how we show our love for God (see John 14:15): “The sum of the Ten Commandments is, to love the Lord our God with all our heart, with all our soul, with all our strength, and with all our mind; and our neighbor as ourselves” (Q&A 42). While the Catechism cannot answer every question a Christian might have about, for example, how the first commandment applies to their life, it gives a wonderful starting point for answering any question—there are four questions and answers on that one commandment!

The Catechism addresses not only outward actions, but the heart that brings them forth. It even brings Scripture to bear in profound and surprising ways, reminding us in its discussion of the eighth commandment that we can even steal from ourselves what God has provided for us. The Larger Catechism expounds what this means: by our slothfulness and “distracting cares” we defraud “ourselves of the due use and comfort of that estate which God hath given us” (WLC 142). This is a call for us to be good stewards of all that God has given.

God’s Word tends to repeat those things that are most important. Over and over again, in a kaleidoscope of expressions, we are told of the person and work of Christ. Repeatedly we are told to love, with the Ten Commandments brought up in various ways (e.g., Eph. 4:28). And so too, the Bible emphasizes prayer as a critical aspect of the Christian life. As Calvin rightly noticed, “prayer digs up those treasures which the Gospel of our Lord discovers to the eye of faith. The necessity and utility of this exercise of prayer no words can sufficiently express” (Institutes, 3.20.2). Or consider B.B. Warfield’s reminder,

…the very act of prayer…will tend to quiet the soul, break down its pride and resistance, and fit it for a humble walk in the world? In its very nature, prayer is a confession of weakness, a confession of need, of dependence, a cry for help, a reaching out for something stronger, better, more stable and trustworthy than ourselves, on which to rest and depend and draw.

Thus, the Shorter Catechism ends with its final nine questions and answers on prayer, using the Lord’s Prayer to bring together what the Bible teaches on this vital practice. It reminds us that when we pray we are relying on what Scripture has revealed about God and his promises. We pray his Word back to Him. We pray his promises back to him. We pray with the gospel in mind—for example, “In the fifth petition, which is, And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors, we pray that God, for Christ’s sake, would freely pardon all our sins; which we are the rather encouraged to ask, because by his grace we are enabled from the heart to forgive others” (Q&A 105).

by Andrew J. Miller

Devotions in the WSC? Sign me up!

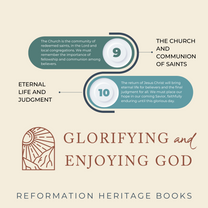

Glorifying and Enjoying God: 52 Devotions through the Westminster Shorter Catechism is now available from Reformation Heritage Books. Get your copy today and begin your devotions through the WSC in just a few days from now.